Antarctica, often seen as a distant, frozen wasteland, is in fact a continent rich in geological history. Initially, the land that would become Antarctica was part of several ancient low-density cratons that merged to form the supercontinent Gondwana in the late Proterozoic era, around 750 to 600 million years ago. For centuries, Gondwana was Earth’s largest landmass until it joined with Laurasia to create Pangea.

The breakup of Pangea, beginning around 175 million years ago, led to the formation of today’s continents. Among the last separations was between Australia and Antarctica around 35 million years ago. This division set Antarctica on a southward path towards the South Pole, while Australia moved north.

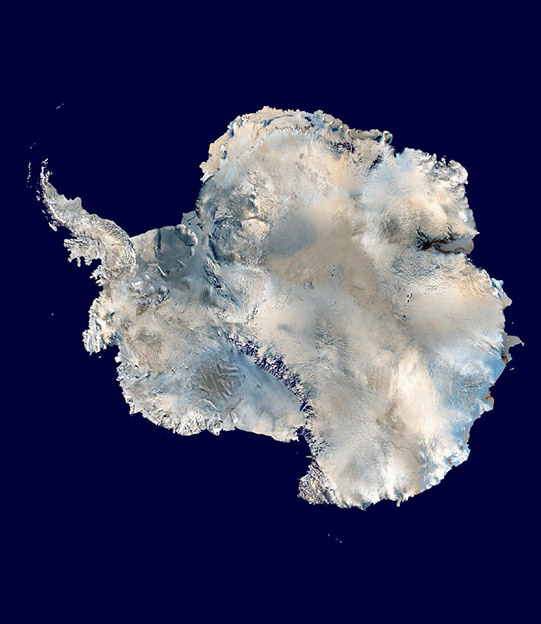

As Antarctica neared the South Pole, its climate began to cool significantly, leading to the formation of glaciers and ice sheets. The development of circumpolar ocean currents further reinforced this cooling, creating a continuous flow of cold water around the continent and contributing to the growth of its vast ice cover, which completely enveloped the land around 15 million years ago.

Once a tropical to mid-latitude region as part of Gondwana, Antarctica’s current geological and biological secrets are largely concealed beneath miles of ice. Some insights into its volcanic, tectonic, and sedimentary history have been uncovered through fieldwork and drilling, but a comprehensive understanding of its past may only be possible if it eventually migrates to warmer latitudes. Today, Antarctica remains a continent of intrigue, holding clues to Earth’s past within its icy embrace.