The emergence of life on Earth remains one of the most intriguing mysteries of our planet’s history. While the exact details of how, when, and why life first appeared are unknown, evidence suggests it arose as soon as conditions permitted. The oldest indications of life are chemical rather than fossil, rooted in the shared chemical architecture of all known life on Earth. Certain biogeochemical processes create distinct patterns in elements like carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphorus, offering unique fingerprints of past life in ancient rocks and minerals, even in the absence of physical fossils.

Life on Earth has a preference for specific chemical building blocks. For example, an anomalous abundance of the isotope carbon-12 (12C) over carbon-13 (13C) in some 3.8-billion-year-old rocks from Greenland provides circumstantial evidence of early life, despite being a topic of debate among scientists.

Recent studies into the Hadean era (4.5–4 billion years ago) suggest that oceans and protocontinents formed early in Earth’s history, potentially creating habitable conditions just a few hundred million years after the planet’s formation. However, the Late Heavy Bombardment, a period of intense asteroid and comet impacts between 4.1 and 3.8 billion years ago, might have hindered or even eliminated nascent life forms.

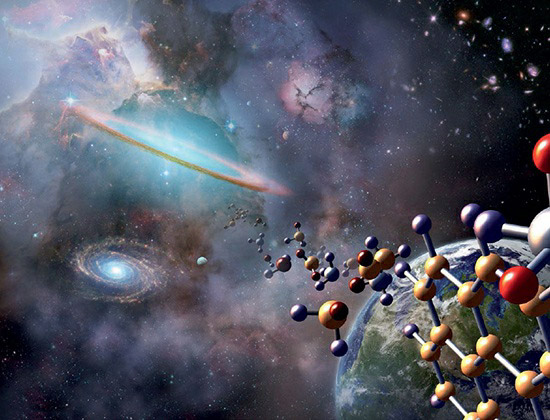

Despite these challenges, life quickly took hold after Earth’s crust cooled, the oceans formed, and the bombardment ceased, leading to a stable environment conducive to life. The rapid flourishing and evolution of life into various ecological niches is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of early life forms. Understanding the initial conditions and requirements for habitability on Earth has now spurred astronomers, planetary scientists, and astrobiologists to search for signs of life on other Earth-like planets, expanding our knowledge of life beyond our own world.