The exploration of the Moon during the Apollo missions from 1969 to 1972 marked a pivotal moment in geology, challenging scientists to apply Earth’s geological principles to extraterrestrial bodies. These missions offered a unique opportunity to test whether terrestrial geology could indeed unravel the mysteries of the Moon’s surface.

The Apollo missions, involving twelve astronauts, yielded over 800 pounds (363 kilograms) of lunar rocks and soils. These samples have been instrumental in shaping the prevalent theory about the Moon’s formation – a colossal impact between the nascent Earth and a Mars-sized body around 4.5 billion years ago.

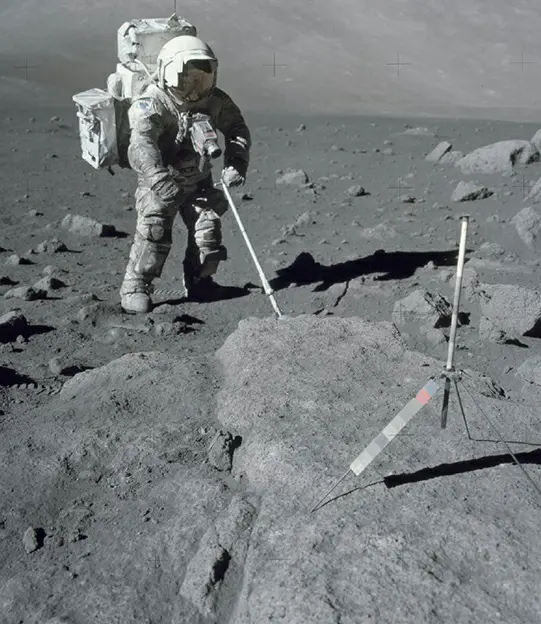

Notably, Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt, a geologist by training, joined the Apollo 17 mission, becoming the first and only professional scientist to walk on the Moon. Schmitt’s expertise in geology, honed at Caltech, Harvard, and the USGS, and his subsequent astronaut training, uniquely positioned him to make significant scientific contributions during the mission. His identification of colored glass beads as remnants of ancient lunar volcanic activity is one such example.

The Apollo missions demonstrated that fundamental geological processes such as volcanism, tectonism, erosion, and impact cratering are universal, extending beyond Earth to shape other planetary bodies. This realization underscored the importance of understanding Earth’s geology to comprehend the geological features of other planets and moons in our solar system.