Around 4.54 billion years ago, the early solar system was a tumultuous place. It was marked by frequent and violent collisions among asteroids and planetesimals—small objects that had the potential to grow into full-size planets. These collisions often resulted in destruction, but in some cases, they led to accretion, allowing these bodies to increase in size. As they grew, their gravity strengthened, pulling in more materials and aiding their growth.

Once a planetesimal reached a certain size, approximately 250-375 miles (400-600 kilometers) in diameter, its gravity would mold it into a spherical shape. This process increased internal pressures and temperatures, further fueled by the energy from continuous impacts on the surface.

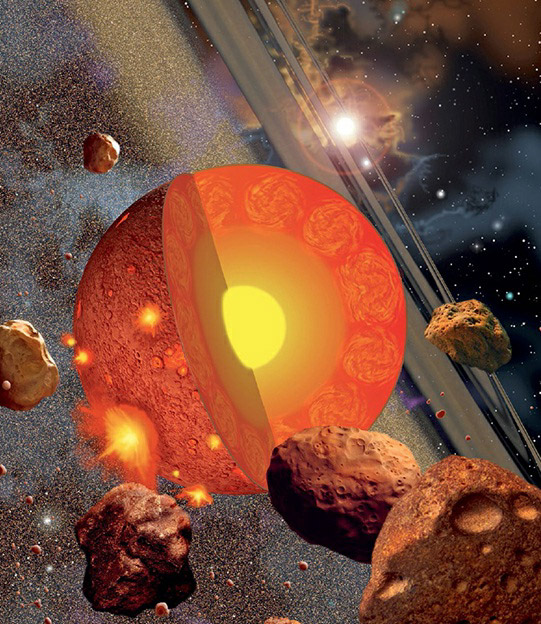

This combination of accretion and internal heating caused a differentiation within these growing bodies. Heavier elements like iron sank towards the center, forming the core, while lighter elements like silicon rose to the top. This differentiation led to the formation of the typical core, mantle, and crust structure seen in rocky and icy planetary bodies.

In planets like Earth, internal heat was also generated by the radioactive decay of certain elements, melting the iron-rich cores. This molten core, combined with the planet’s rotation, created strong magnetic fields. Earth’s magnetic field played a crucial role in making its surface habitable by protecting it from harmful solar radiation.

Over time, Earth’s core has continued to evolve. While the outer core remains molten, the inner core is believed to have cooled and solidified about 1 to 1.5 billion years ago.