Over 200 million years ago, the Earth witnessed the second-most recent of its five known large mass extinction events at the end of the Triassic period. This event, spanning tens of thousands of years, resulted in the extinction of at least half of the species then existing on Earth. On land, the archosaurs, a dominant group of sauropsid vertebrate amniotes during the Triassic, were particularly affected.

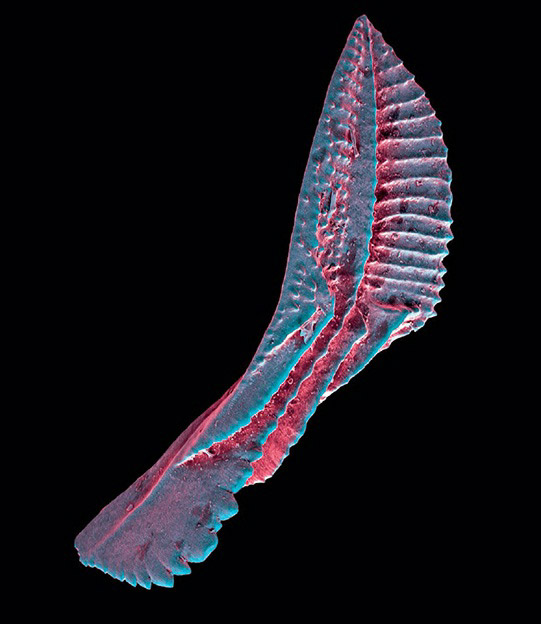

In marine environments, the extinction was equally catastrophic, with over a third of the genera becoming extinct. This included a significant number of large amphibians and the entire class of eel-like vertebrates known as conodonts. The disappearance of the conodonts, long-standing creatures that had survived even the more devastating End Permian mass extinction, remains an enigma.

The causes of the End Triassic mass extinction are still debated. While a large asteroid impact is a potential explanation for the sudden global loss of species, no definitive impact crater or geological evidence has been found. Other theories include massive volcanic eruptions leading to an increase in greenhouse gases, possibly linked to the breakup of the supercontinent Pangea. However, many proposed climate change scenarios seem too gradual for this event.

Despite the widespread devastation, some species survived and thrived. Among the surviving archosaurs were the precursors to dinosaurs, which went on to dominate land for over 130 million years, from the Jurassic until the next mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. Mammals, another group that endured the End Triassic extinction, continued evolving traits and behaviors that would eventually help them survive future catastrophic events, unlike the non-avian dinosaurs. This mass extinction marked a significant shift in Earth’s biological history, setting the stage for the rise of new dominant species.