Asteroid impacts have long been recognized as significant geological forces, shaping the history of Earth and other celestial bodies. The creation of our Moon, the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, and other mass extinction events are attributed to such colossal impacts. Recent incidents like the Tunguska event in 1908 and the Chelyabinsk meteor in 2013 serve as reminders of the ongoing threat from space.

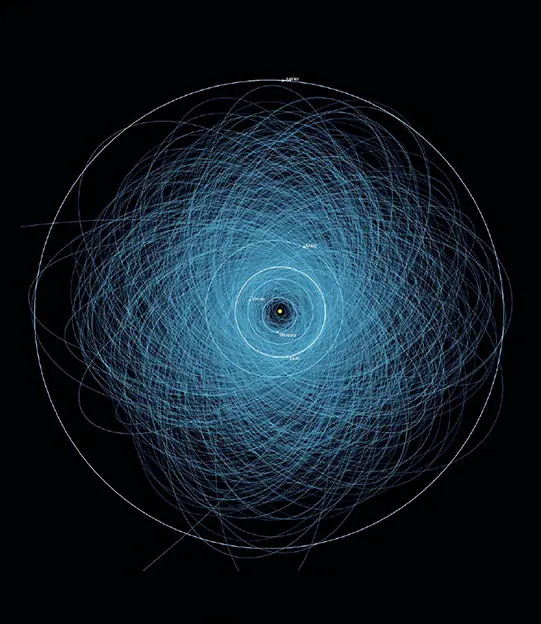

The critical question is: when will the next large impactor hit Earth, potentially triggering a major climatic or biological catastrophe? Efforts by astronomers, planetary scientists, and planetary defense experts are focused on identifying and assessing Potentially Hazardous Asteroids (PHAs). By 2011, surveys had identified 90% of asteroids capable of global catastrophe. Ongoing efforts aim to expand this survey to include smaller asteroids, which could still cause significant regional damage.

Statistically, a “dinosaur-killer” asteroid, approximately 6 miles in diameter, is expected to strike Earth every 100 million years. This suggests a reprieve from such a catastrophic event for at least 35 million more years. However, smaller asteroids, about 0.6 miles in diameter, with the potential to unleash energy equivalent to thousands of atomic bombs, are more frequent, occurring every 500,000 years. These could cause considerable local destruction and climate disruption.

The uncertainty surrounding the timing of these impacts raises questions about our readiness to handle such events. With ongoing research and advancements in technology, the hope is to be better prepared for when the next significant asteroid impact occurs.