Deep beneath the ocean’s surface lies a realm of extraordinary geological activity, where the Earth’s internal heat is vented through deep-sea hydrothermal vents. These underwater volcanic features, pivotal in oceanography, were discovered in the 1970s near the Galápagos Islands. Researchers from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, using the submersible vehicle Alvin, unveiled a world where superheated water merges with the cold ocean, creating unique ecosystems.

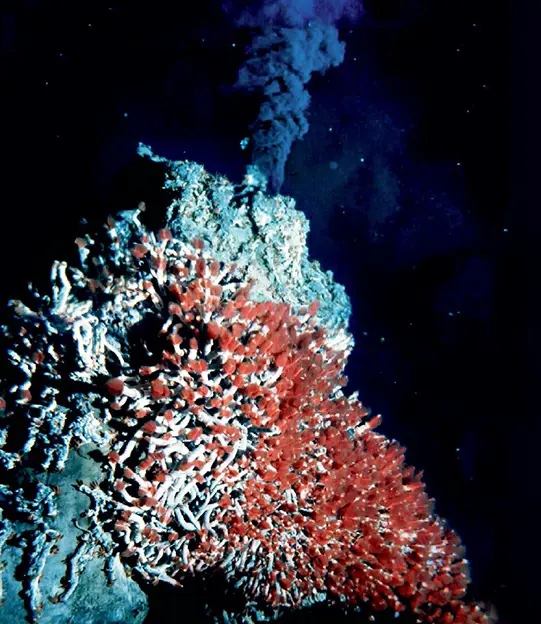

The exploration of these vents revealed that seawater, seeping into the Earth’s crust and heated by magma, re-emerges onto the seafloor. These hydrothermal vents can range from mild temperatures, just slightly above the surrounding waters, to the intensely hot black smokers, where water can exceed 700°F. These black smokers form distinctive mineral-rich towers, contrasting with white smokers that deposit lighter silicate minerals.

Surprisingly, these hostile environments host diverse life forms. The base of these deep-sea ecosystems comprises bacteria and archaea that harness sulfur compounds for energy through chemosynthesis, a process independent of sunlight. This discovery has expanded our understanding of life’s resilience and adaptability, showing thriving communities of tube worms, clams, and shrimp flourishing in extreme conditions.