In 1851, French physicist Jean Bernard Léon Foucault conducted a groundbreaking experiment that provided tangible proof of Earth’s rotation. His approach utilized a simple yet ingenious method: a pendulum. Foucault’s experiment took place in Paris’s Panthéon, where he set up a long, heavy pendulum. The essence of the experiment lay in observing that the pendulum, once set in motion, maintained its swing direction while the Earth rotated beneath it.

Foucault capitalized on Newton’s first law of motion, ensuring the pendulum would remain in the same inertial reference frame. As a result, observers could visibly see the Earth’s rotation in action, as evidenced by the changing direction of the pendulum’s swing relative to the Earth’s surface. This experiment was pivotal in transforming the abstract concept of Earth’s rotation into a visible, understandable phenomenon.

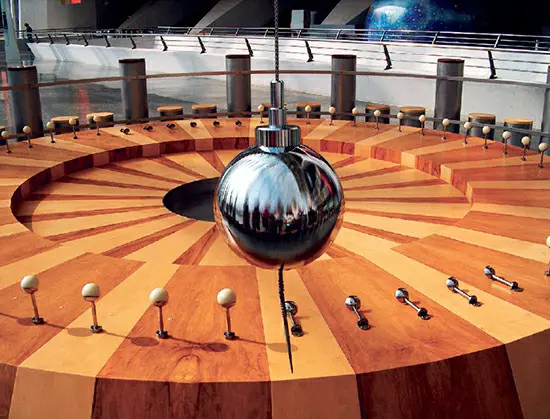

The following year, Foucault further enhanced his exploration of Earth’s dynamics by perfecting a gyroscope, a device that measures velocity and orientation. The simplicity and brilliance of Foucault’s pendulum made it a sensation of the nineteenth century, and replicas of this experiment are still showcased in numerous universities, museums, and science centers worldwide.