The late 19th century witnessed a flurry of groundbreaking discoveries in European and American physics laboratories, particularly in the realms of electricity and magnetism. This era of innovation led to the accidental discovery of a mysterious new form of radiation by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, while experimenting with high-voltage cathode-ray tubes. Röntgen named this radiation X-rays, unaware of the profound impact this discovery would have.

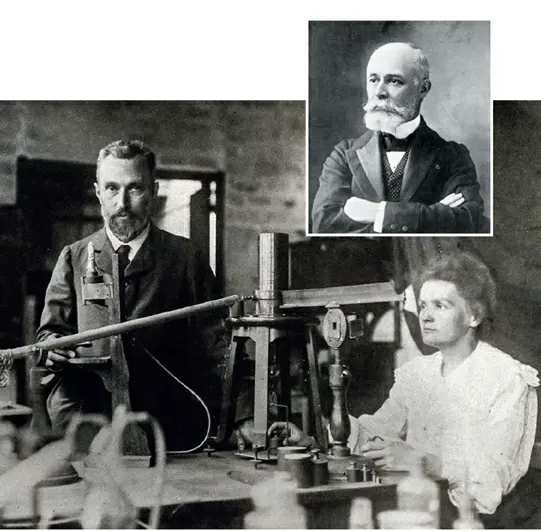

Simultaneously, French physicist Henri Becquerel, intrigued by the potential relationship between phosphorescence and X-rays, embarked on a series of experiments in 1896. His work led to a groundbreaking discovery: uranium salts emitted radiation spontaneously, a phenomenon he identified as radioactivity, distinct from X-rays.

This discovery of radioactivity captured the attention of Pierre Curie and Marie Skłodowska Curie. Marie Curie, in particular, made significant strides in understanding radioactivity, leading to the discovery of two new radioactive elements: polonium and radium. The remarkable contributions of Becquerel and the Curies to the field of physics were recognized with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, making Marie Curie the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize and later, the only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields.

The concept of radioactivity opened a new chapter in scientific exploration, serving as a natural “clock” to measure the age of Earth, the Moon, meteorites, and by extension, the age of the solar system. The precise measurement of radioactivity has allowed scientists to estimate the age of the Earth at approximately 4.54 billion years and the Sun at about 4.568 billion years. The pioneering work of Röntgen, Becquerel, and the Curies not only revolutionized our understanding of the natural world but also laid the foundation for numerous scientific advancements.